You say “disruption,” I say “JUST disruption”

Disruption is a big topic today in every industry. Musicians and the music industry are wrestling with the disruption of digital and streaming content. Traditional media outlets (and our political and social systems) are reeling from the disruptions caused by social media and user-generated content. Autonomous vehicles are poised to disrupt auto making, trucking, transportation systems, and our communities.

The legal sector is no exception. A variety of forces—the rise of digital technologies and artificial intelligence, new models for delivering legal services, and dramatic changes in the US economy, to name just a few—have generated seismic waves that will reshape legal services and legal education for years to come. Law schools and every part of our legal profession are scrambling to respond and get ahead of these changes.

Too often, the conversation around “disruption” seems to treat disruption as an end in itself. Likewise, any change is too-often called an “innovation.” As we talk about disrupting something as critical as our legal system, we need to be very clear about the aim of disruption. It can’t be enough to merely disrupt or change (even if you call that change an “innovation”) if the end result is no better, or even worse. In my view, we need to think beyond disruption for its own sake and set our sights on something I call “JUST disruption.” In other words, disruption that promotes justice. For instance:

- According to a 2016 report by Deborah L. Rhode, “… [o]ver four-fifths of the legal needs of the poor and a majority of the needs of middle-income Americans often remain unmet.” These percentages are even higher in many other parts of the world. How can we harness the forces of just disruption to increase access to justice?

- At a time when our legal institutions are not keeping pace with the changing face of our population, how can we use just disruption to create a legal system that mirrors the diversity of our communities?

- At a time when young people are rightly asking how their investment in higher education will translate into career opportunities, economic security and greater social impact, how can we leverage just disruption to rethink how our legal institutions are structured and open up greater opportunity at every level of the profession?

These are just a few of the just disruptions that I want to see.

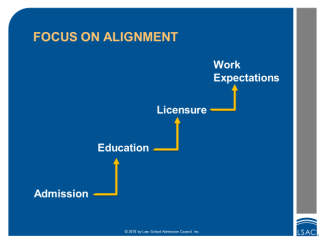

As we focus on just disruption, one approach that will help us accomplish more is to view the journey from prelaw to the legal profession holistically and to seek alignment across its various stages. Thus far, we have too often focused on only one stage and not on how they fit together.

For example, we often conflate skills needed to thrive in the profession with those we should be looking for in admission. That sells legal education far short. If the skills we look for at admission are the same ones that are necessary to thrive in the profession, then what are we doing with three years of law school? Admission should instead focus only on the most fundamental abilities necessary for success in law school (e.g., reading comprehension, critical thinking), whereas legal education should then build on that solid foundation so that graduates acquire the knowledge, skills, and values for professional success.

I agree that law graduates should be able to negotiate a contract, read a financial statement, understand a complex problem that has technological dimensions, and write an effective client letter, but that does not mean we need to test these skills at admission. Let’s include those skills in the curricular and co-curricular programs. At the outset, let’s keep the door open wide and then make sure we add as much value as possible during law school, including designing appropriate academic support programs that help bolster skills that may not have been fully developed prior to law school.

Likewise, if we focus on the whole picture, we can better assess the purpose of licensure. If its purpose is protection of the public—the same goal that ABA accreditation is designed to serve—then what does it add that a healthy system of accreditation cannot? Does our accreditation process need adjustment? Should licensure be more narrowly directed only at those seeking bar admission from unaccredited law schools? Should it be in stages so that, more like medical school licensure, it builds sequentially on a student’s skill acquisition? A focus on the alignment between the various stages of a lawyer’s journey is more likely to lead to innovations that advance justice rather than prompting isolated “disruptions” that miss the bigger picture.

To be sure, the seismic changes in our economy mean that the skills and experiences our law schools traditionally have imparted must be adjusted to include additional skills that new lawyers need for success. Many law schools are working hard to stay abreast of these changes, while also rightly continuing to emphasize the core skills that legal education is unmatched at advancing. Even more just disruptions may be needed. Despite many great changes, legal education remains too heavily focused on litigation, including in clinical programs that provide students vital experience while also helping address our huge access to justice gap. Despite recognition of technology’s transformative influence on law and all fields, legal education largely fails to equip graduates with the skills to effectively deploy even basic technologies that can leverage their work, and likewise insufficiently familiarizes its students with sophisticated technologies, such as artificial intelligence, that are raising some of our most complex societal questions. Most law graduates don’t need to be “tech people” themselves, but they sure need to understand technology well enough to help their clients who are grappling with its impacts and opportunities.

These are just a few ideas on how we might work toward more just disruptions in our systems of law and legal education. My main point today is to call us to keep justice in view as we make our innovations and disruptions. We are not, after all, making gadgets or even figuring out how to order more of them and get them delivered faster. We are working to advance the rule of law and build the future of justice. While that goal certainly needs the very best of our creativity and openness to change, it also deserves the very best of our values.